Spirit made out of cereals. This statement is present on many bottles of years ago, and mentions one of the few, yet inflexible rules to be applied to this spirit. We talked in the past about whisky aging, when the transparent liquid, the so-called new make spirit, enters the cask and is kept there for several years, at least three (or 2 in the USA). But what is it made from? Which are the raw materials involved, and which transformations are those experiencing?

Whisky comes by law from cereals: barley, rye, corn and others, as long as they are cereals. For other spirits rules can be more flexible, but not for whisky. Regarding barley, the fundamental basis of Scotch Whisky and of other products from all over the world, the first phase after plantations and harvesting is the malting process, which has been known to mankind for thousand years, passed down from Mesopotamia to the entire world.

Barley, though looking pretty dry, contains high quantities of starch; this starch is useful for the germination, which is plant reproduction. The sprout is ideally born in spring, when rain humidity and temperature favor the reproduction. It makes usage of the starch to grow by transforming it into maltose, a sugar which is critical for whisky. Man acts in this specific phase to limit the sugar consumption by the sprout: everything is artificially controlled and the sprouts themselves are kept in water for a long period (approx. two days) then to be laid on malting floors and manually or mechanically turned. Barley is then induced into germination to transform starch into sugar, and it is exactly in this moment, when sugar quantity is maximized, that the process is interrupted: a practice which may appear unfair but well justified in your next whisky sip. The newborn malt is indeed dried in an oven, the so-called kiln. We already talked about peat; the peat-produced warm air can indeed determine how the resulting malt has to be peated. Malt remains in the oven for a couple days to complete this phase.

The second phase envisages malt transformation into a sort of rough flour by usage of a mill, or of a grindstone: this crumble, named grist, is paired with water and this substance, named mash, is poured into the mash tun: each distillery features a different process, with different proportions, different mash tuns and different mash storage temperatures. Water is also fundamental: each renowned distillery was founded near to large quantities and high quality spring water. Iron-rich water is not very well accepted, calcium-rich one is preferred. A second transformation takes place into the mash tun, where sugar transforms the mash into a dense must. Adding specific yeasts to this substance fermentation is started, one of the most critical processes of the entire procedure: each distillery follows different, strictly documented rules, using proprietary, selected and constantly controlled yeasts. The chemical reaction is pretty slow (some days are required) and it transform mash sugar in carbon dioxide and, finally, in alcohol. Mash thus becomes wash: this sort of beer (in the US it is actually named beer) bears an 8 to 20 degrees alcoholic percentage; in some distilleries, during the manufacturing site tour, it is possible to taste it, picking up a sample directly from the mash tun.

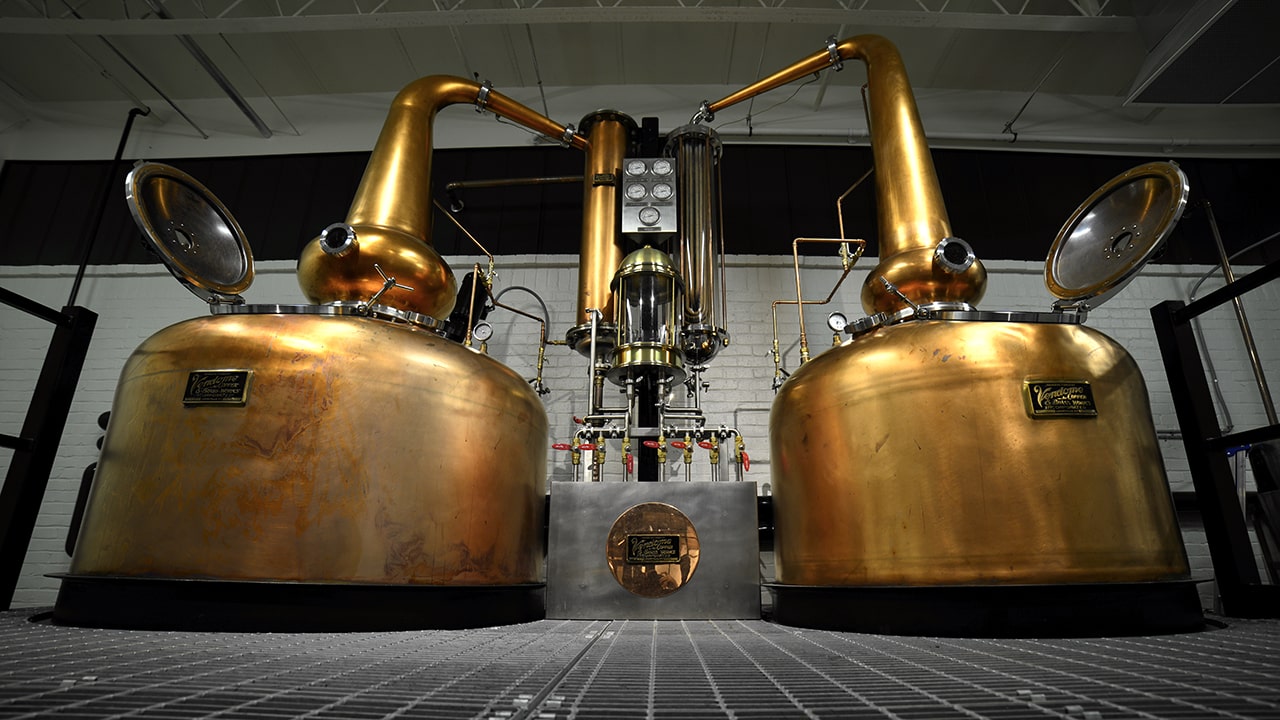

We reach then the final phase of this process: distillation. Different still types exist but, to avoid confusion, we will only describe the two main distillation methods, meaning continuous and discontinuous. The discontinuous distillation includes a linear process which, from wash, will directly bring to the new make spirit, ready to be poured into the cask for aging. Scotch whisky is based on double distillation, with the exception of some distilleries (Auchentoshan, Hazelburn, Springbank) using triple distillation. The so-called Pot Still resembles an onion, and it is made out of copper: shape can vary even in the same distillery; each company is proud of their stills, and keeps them active for several years. Substitution is pretty complex, so that many times the old still shape, and even the damages accumulated during the years are replicated. The copper of which the still is made helps in eliminating the sulfur component produced by the cereals, a step which is mandatory to avoid these notes into the final product.

The still is filled with wash and warmed: warming, which was once upon a time by direct fire, is today controlled by several steam coils, to make the temperature constant and easily controllable. This procedure leads wash into boiling, and to the creation of alcohol vapors: alcohol boiling temperature is 78°C (172°F), lower than water one. Vapors are moving upwards into the still, reaching the highest part, named lyne arm. Each still is different, however let us try to generalize: a high still originates a lighter spirit, as heavier vapors are not able to reach this high point, thus remaining in the body of the still, such as for Glenmorangie. On the opposite, a lower height originates a heavier spirit: Lagavulin can be a good example.

At this stage vapors are driven into a condenser, a sort of large tube cooled by water to transform back the vapors into a liquid. Today’s condensers are few meters long; only some distilleries, a few of them, use a longer than 20 meters, water immersed coil, the so-called worm tube. This phase as well impacts the final result: the longer the contact with copper, the richer and more full-bodied the spirit will result. This first distillation originates the so-called low wines with an alcoholic percentage between 20 and 25 degrees, however still insufficient to be considered as new make spirit. It is thus necessary to move to a second distillation using smaller dimensions stills, called spirit stills. From the second distillation, the final product is obtained, but it is in this phase that the master distiller is carefully following the distillation evolution, eliminating the results of the initial (foreshots) and final stages (feints) of the distillation. Both need to be avoided as they would give a non-targeted character to the whisky; however they are in any case re-introduced into a container and distilled again in the following run.

The liquid now obtained is new make spirit featuring an alcoholic percentage of 70°C (158°F). The new make spirit can be added water in order to reach the famous 63.5° threshold, which is used by many distilleries but not mandatory. The last step is the pouring into the cask: our new make spirit is thus ready for aging, which will transform it into whisky, to end up in our glass. The continuous distillation uses column stills and continuously produces high alcoholic percentage without the requirement of eliminating the results of first and final stages of the distillation process. Wash is actually poured from high in this container and meets a warm air flux proceeding in the opposite direction. Warm air makes the alcohol evaporate and drives it upwards, while water does not evaporate and drops down. Inside the still some drilled metal foils are blocking the wash. Each layer included between one foil and the next one initiates alcohol evaporation; the residual wash keeps moving towards the lower layer, and will be exposed to the vapor, which will make the residual alcohol evaporates, and so on up to the base of the still.

Generally speaking, and avoiding many technical notes regarding the involved procedures, this is the basics of the steps by which simple cereals become a white spirit, which is however bearing some of the characteristics that the cask, in years of marriage, will bring to maturity and, finally, in our glass.